The Survival-Vital Matrix | Trauma Work

A New Horizontal Line

So far we’ve seen how the four questions in the quadrants of the matrix are highly flexible and can be tailored as the situation demands, the horizontal line on the other hand, has remained the same. But what if toward and away were not the only workable labels for the horizontal line?

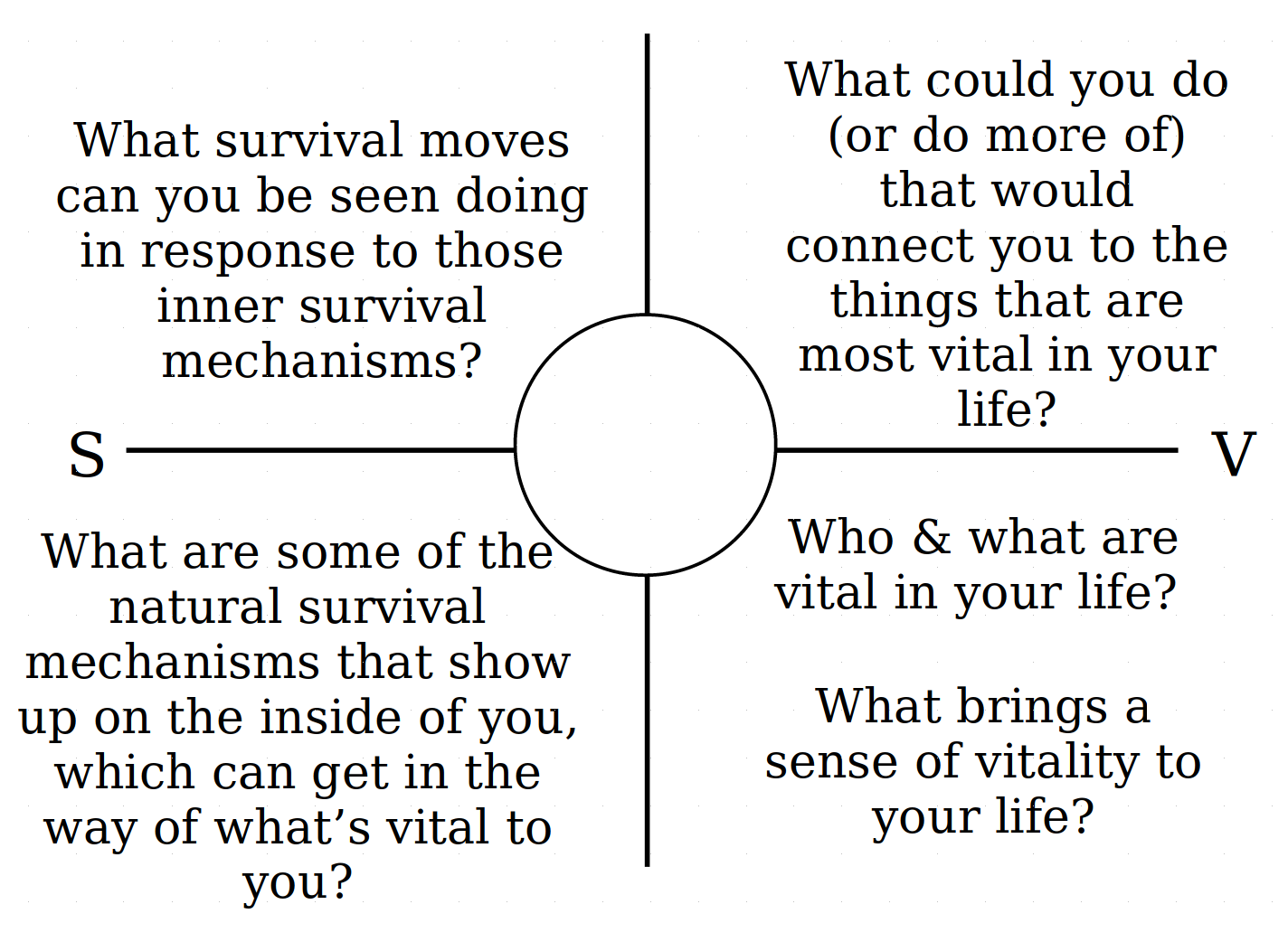

Acknowledging the inherent weakness of toward and away as verbal labels (see blog post from my sister site Is Toward & Away The Most Workable Language?), I set out to create an alternative way of presenting the matrix that could overcome the challenge of misconstruing the horizontal line. What I came up with I now refer to as the Survival–Vital Matrix, or the S–V Matrix for short.

In this matrix the letters S and V are placed on either end of the horizontal line, standing for survival and vital. Another difference is that this horizontal line does not include arrow heads.

Think of the word vital, what does it evoke? That which is vital is the most important, necessary, and essential. When you go to the doctor or the hospital they check your vitals first and constantly monitor them. Vital comes from the Latin word for life, vita, and for centuries vital and vital-ity have referred to quality of life, particularly the characteristic energy and rigor of life. This dual meaning is a complement to how traditional ACT conceptualizes values. When we are in touch with and acting in accordance to our values our life has a sense of vitality. When it comes to the ACT Matrix, the word vital captures well the question of the lower right-hand quadrant, Who and what are important to you?, as well as type of actions that would appear in the upper-right quadrant.

Now think of the word survival. Notice the familiar root there in the middle of it. Sur-viv-al, from vivere, which means “to live”. Survival means continuing to live, in spite of hardship, difficulty, or danger. That hardship, the difficulty, the danger, sometimes that shows up inside of us. And the things we do to survive, our actions, they’ve developed for a reason. They were functional once, or as functional as they could be.

Put these two words together and we have a sense of life that is vibrant and essential, and a capacity to keep going despite the hardships that are inevitable. That sounds a lot like psychological flexibility to me.

The terms survival and vital do not imply opposition, or any directionality, which is why the arrows are no longer needed. The terms work as a tandem. You can survive but not have a vital life, you can have a vital life but you need to survive in order to enjoy it for long. Some things which are necessary for survival, such as eating, can become vital parts of living. At the same time the terms require workable balance. The instinct and need to survive can override or impede our sense of vitality (“I can’t leave my house because it’s dangerous out there!”). The desire and search for vitality can conflict with what is traditionally considered safe (mountain climbing, sky-diving, certain sexual practices like BDSM).

Thinking in terms of survival and vital as compared to toward and away requires some conceptual shifts, but overall they map onto one another fairly consistently. You might think of the S–V Matrix as another layer to the ACT Matrix. Essentially everything that you have learned in this book applies to this version as well. Keeping with the flexible nature of matrix work, you could theoretically use the S–V Matrix solely as an alternative to the traditional ACT Matrix, or use it as an addition to ACT Matrix work. I find that the S–V Matrix works particularly well with trauma presentations.

Setting up the S–V Matrix for the first time

Setting up the S–V Matrix works in much the same way as the traditional ACT Matrix. Only some language needs to be changed. When setting it up in the beginning, a metaphor explaining toward and away is no longer necessary, but a similar one can be used to describe the difference between survival and vital. An animal exhibits both survival and vital instincts and actions. Our helpful rabbit from the traditional matrix can show up here too. What is vital for a rabbit? What are some things that a rabbit could do that would make its life feel vital? For a rabbit this might be mating and endless bounties of carrots and cabbages. When the predator or hunter comes, what are some of the survival mechanisms and actions that a rabbit engages in?

Just as in the traditional matrix, it turns out that we humans are a lot like rabbits, we have things that make our lives vital, and we have instincts for survival. We engage in actions that support both vitality and survival. The main difference between us and a rabbit is that we have that dual world we live in of inner and outer. There are outer things we do for survival and for vitality, and there are inner things we do too. On the outside for survival, we can run, hide, fight, freeze up, play dead, and all sorts of other things. On the inside for survival, we plan for the future, rethink the past, problem solve, try to control, and on and on. All of these things are survival strategies in the end. We ruminate, we worry, we panic, and more. For vitality on the outside, we engage in external behaviors that are easy to see like go to concerts, create art, explore, etc. On the inside, we contemplate, love, philosophize, meditate, plan for the future, recall the past, and all kinds of other things. While we are biological creatures beholden to our evolutionary history, we have a unique place in the world as humans. Most wouldn’t argue with the idea that at least on the level of sheer quantity of experience, humans take the cake when it comes to inner stuff. Reconciling our inner and outer experience is still the main aim of S–V Matrix work.

Everything that you would see as responses in the quadrants of the traditional matrix are valid here. The lower right-hand quadrant simply becomes:

Who & what are vital in your life? And as a follow-up, What brings a sense of vitality to your life?

Who and what is of absolute importance, essentially necessary, to make your life vital and meaningful? What would feel fatal to you to do without? The questions you can ask clients here are boundless.

The lower left-hand quadrant becomes:

What are some of the natural survival mechanisms that show up on the inside of you, which can get in the way of what’s vital to you?

Fear of course is one of the most fundamental survival mechanisms. The other old friends that we see in the therapy room like anxiety, stress, anger, and even self-critical thoughts, and shame have roots in survival. I would venture to say that all of our inner experience at one point had a function that pointed toward safety and survival. That function may be much different now, and it’s important to acknowledge that no internal experience is wrong or bad, we can often (but not always) trace back our experiencing to events from the past. Framing these internal experiences in this way is necessary for the S–V Matrix to work.

In the upper-left quadrant you can ask the question:

What survival moves can you be seen doing in response to those inner survival mechanisms?

Survival moves in this context are any behaviors meant primarily to respond to the inner content in a manner that is protective. This would include fight, flight, and freeze responses. Many of the common behaviors you would see in this quadrant of the matrix are likely to appear here in the S–V Matrix: shut down, cut people off, isolate, etc.

The upper-right quadrant of the matrix is almost the same as the traditional matrix:

What could you do (or do more of) that would connect you to the things that are most vital in your life?

The horizontal line still expresses workability, and individual actions can be broken down and analyzed as done in the traditional matrix.

One of the main reasons I took to the traditional ACT Matrix was how effortless it made the ACT concepts of creative hopelessness and workability to the client. By the end of that first interaction with the matrix a client is often in a place where they have begun to assess the workability of their own actions, understand the effect their actions have, as well as understand stuck loops in their life and therefore, hopefully, how now might be a good time to do something differently. It’s a one-two punch of workability and creative hopelessness. The S–V Matrix retains all of that power and benefit, with the added component of tying language into the picture right off the bat. For example, the ability to think ahead into the future, and the ability to think over the past are two very powerful skills which also act as survival mechanisms. If we couldn't think ahead or learn from the past through thought rather than direct re-experience, we wouldn't make it too far. Our mind’s ability to harness language in such a way has kept us alive and at the top of the food chain, but as it happens it’s also the main factor of how and why we can get stuck in life. Adding this component into the presentation of the matrix allows clients to notice their mind in a way they likely haven’t before.

Working with trauma with the traditional ACT Matrix

The ACT Matrix was initially conceived as a “trauma sorting tool”, used with veterans who experienced traumatic events from their time in the military. As a framework and tool, the traditional matrix works well to break down experiences and symptoms of trauma in a nonjudgmental and functional way. The flexibility of the matrix allows work to occur both broadly and acutely in the sense that traumatic experiences and the after effects of trauma can be examined and processed over the long-term, and acute events such as flashbacks, panic, and dissociation can be handled in the moment. Broadly, the matrix cues a more functional kind of noticing while shaping workable behavior. For example, when we set up the matrix the standard way we have a wide representation of an individual’s life with which we can track the ways trauma shows up.

Often the trauma memories are placed in the lower left-hand quadrant. Over time, and with consistent practice, clients can learn to see the loops of their trauma and how they work for them. Gradually they can start interrupting those unworkable patterns of behavior and engage more purposefully in actions that move them toward a meaningful life not ruled by their trauma. Step-by-step, clients regain control over their lives, and come to an understanding that trauma is an aspect of their history that can be responded to in a way that works for them.

In an acute sense, say in the middle of a panic attack, flashback, or period of intense hyper-arousal, the traditional matrix can be used to sort out this experience as it happens. When we are in the middle of these intense emotional experiences it can be hard to see that anything else is going on at all, not only that the world is still turning, but that the experience of the distress itself contains a wide range of content. Our awareness of the current moment can be narrow or broad the same way a beam of light can be a laser pointer or a wide flashlight. Practicing widening out this sense of awareness happens as a matter of course through matrix work, but should also be done as a discrete skill practice in neutral or benign situations often (See chapter on present moment contact). When we broaden our awareness to include more and more, any single distressing point becomes easier to bear. Consider the following scenario of a former combat veteran now adjusting to life back home:

Zaafir served as a U.S. Marine for twelve years, and had three tours of duty oversees in high conflict areas. During this time, astute awareness of surroundings meant the difference between life and death. In the small communities in the Middle East that Zaafir was stationed in, he had to be constantly aware of any irregularities in the ground ahead of him, and simultaneously scanning the rooftops for snipers. He had been in units where men were fired upon seemingly out of nowhere.

Now that he was back in the U.S. and attempting to build a life as a civilian, the memories, training, and instinct, born out of war stayed with him. He often found himself needlessly assessing risk in any building he walked into, overreacting to loud sounds out in public like fireworks, having flashbacks to a moment when he saw civilians gunned down.

Zaafir has been working with a therapist at the Veteran’s Affair’s office, and attending group sessions, for the past three months to process his traumatic experiences and get a better handle on these symptoms. His therapist introduced him to the ACT Matrix and Zaafir took to the method quickly. He began viewing his life through the lens of the matrix, with at least one deliberate practice of the matrix each day.

Zaafir recounted to his therapist with excitement a moment from the previous day in which he used the matrix to help with a flashback, and circumvent a panic attack.

Zaafir: I was having breakfast with Maria at a diner that she’d been wanting to try forever. We were sitting across from each other and I was near the window. I started looking outside and saw across the street a man standing on the roof of another building. I was convinced that he had a rifle, and at that moment everything started to rush back in. I was back watching those people die.

Therapist: How was this time different than the times before?

Zaafir: Normally when this happens I’m so focused on what’s going on, the shots in the distance, the people falling, and how I’m frozen, unable to move at all. When it hit me this time I could see all the same things, but then out of nowhere I realized that it was happening. I knew it was a memory and inside of me rather than outside. I had this image in my head of the matrix, and this stuff was showing up in the bottom left box.

Therapist: Wonderful!

Zaafir: And from there, I don’t know I just started to fill in the rest of the boxes with what I was seeing in the flashback. The people, the women and children, they were important to me. Protecting them and my guys were important to me. And I was frozen I was stuck, that was in the top left, but I also was looking at the people and not where the fire was coming from. I should have been trying to track the fire, and also covering, that’s in the top right box. And then there was me, I was the one kind of looking at it from above or something. I could see the whole situation.

Therapist: So you were able to be in the flashback, but you had this kind of additional awareness of what was going on.

Zaafir: Yes. And then I was back in the diner looking at this man on the roof, and I was able to see him more clearly. He was just doing some repairs on the roof. I was here, I was safe, I was sitting with Maria eating eggs. She was important to me, right there and then. Before, this flashback would have lasted much longer, it would have looped, and it would have taken me at least an hour to recover from it afterward, with the panic. This time, I just looked at Maria and kept eating. I don’t even think she noticed. Here we see Zaafir, through consistent use of the matrix as a tool for looking at his life broadly, was able to use the matrix in a very acute circumstance to sort the content of a traumatic experience as it was happening. In essence, he was widening his awareness from a single point out into the context in action. Note that Zaafir’s ability to use the matrix for this specific flashback was only possible because of the multiple repetitions of using the matrix on a daily basis and becoming so familiar with the four quadrants. The power of the matrix is in the repetition.

Working with trauma with the S–V Matrix

The Survival–Vital Matrix complements this process of trauma work by placing our natural responses to trauma front and center. In the lower left-hand quadrant, we place our survival mechanisms, instincts, and other natural responses to life’s hardships. This quadrant is the perfect place to introduce some psychoeducation on trauma and how the body responds to it. Fight, flight, and freeze, polyvagal theory, and any other model of responding can be used here as a part of conceptualizing trauma. The matrix should not interfere with these conceptualizations, but rather serve as a framework for wider contextualization.

The more clients know about what is happening in their experience after a trauma, and how it is not abnormal, the better they will be able to view it as a functional component in the context of their lives. When survival mechanisms are framed as normal, and in fact typical, we can more easily treat them with compassion, understanding, and respect.